Biking Highlights

Hokkaido. Northern most island, full of vast nature and winding roads. Sapporo has a vibrant city center, Furano has beautiful flower fields, and Asahikawa has one of the greatest zoos. There is also Bear Mountain - your best bet to see a lot of bears up close. These are all connected by winding roads in forests with great viewpoints that overlook the landscape.

Nikko National park. Beautiful roads through forests, with many cute bridges, waterfalls and lakes. Less vast than Hokkaido, but arguably more scenic.

Tokyo, Yokohama, Kyoto. You’ll find many guides on these cities everywhere. I stayed 2-3 days and biked across, and yet I still saw only the tip of the iceberg. Especially Tokyo feels like 10 major cities merged together, or like an open world game with endless activities at anytime in any neighbourhood. Biking through it is no joke, but worth it.

Mount Fuji. Probably very pretty. I wouldn't know as it was shrouded in clouds when I biked around it. Also, know that there is no iconic snow cap from late June to October.

Naoshima. A small island full of contemporary art, both outdoors and in musea. It’s really cool to visit, a welcome change, and ideal for biking or even walking. Easily reached by ferries from both Honshu and Shikoku.

Shimanami Kaido. A dedicated 70k bicycle path that connects 6 smaller islands between Honshu and Shikoku. Here you suddenly meet plenty of fellow bikers and ride on what is probably the best bike infrastructure in Japan. The views are stunning, especially when crossing the dramatic bridges that connect the islands. The route reminded me of northern Norway, but with more people and better weather.

Japanese Language

Worth it? Learning Japanese from scratch takes years obviously, but learning a set of 20 short phrases is worth the effort for any trip to Japan. Both from a practical standpoint, as well to set a friendly tone with people you meet.

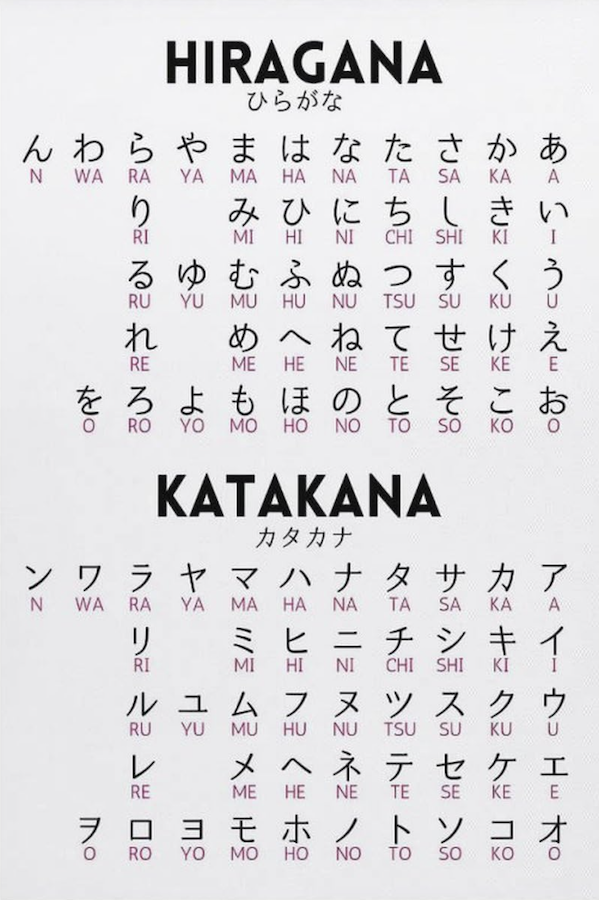

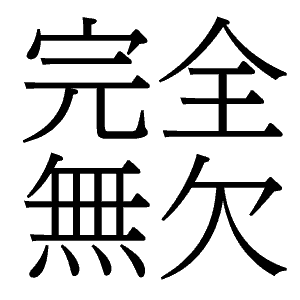

Writing systems. Japanese has three commonly used writing systems which you'll see everywhere: Hiragana (for native Japanese), Katakana (for loan words) and Kanji (adapted Chinese characters to describe more complex concepts). The first 2 are relatively easy with 46 symbols each, and can be learned in a week with flashcard apps. This is quite fun as you start recognising words in the street while riding. The third one, Kanji, is way more complex with over 2100 different symbols. This is what takes years.

Sound system. Instead of single phonemes like in western languages, 'kana' are the most granular phoneme combinations. They combine a consonant and a vowel, like 'ni' or 'go' (the phoneme n is the only exception which is used standalone). Every western name or loan word is 'mapped' unto whatever lies closest in the Japanese sound system. For example: restaurant becomes resutoran, smartphone becomes sumaho. This is also how you would translate your name to Japanese: James becomes Jeemuzu.

Complexity. As mentioned, the Kanji writing system has many complex symbols. Secondly, as the native Japanese has no common ground with Germanic or Roman languages, every word is to be learned from scratch. This excludes loan words, which are often recognisable. Thirdly, Japanese knows a lot of registers corresponding with various degrees of politeness and formality. This goes way beyond the tu/vous distinction in French. Words and verb inflections will change continuously based on what level of formality is appropriate.

Communication with locals. Knowing a limited set of phrases will get you a long way. In cities or touristy places, locals will know some English but elsewhere it's often not the case. When having trouble to communicate Google translate will help you out.

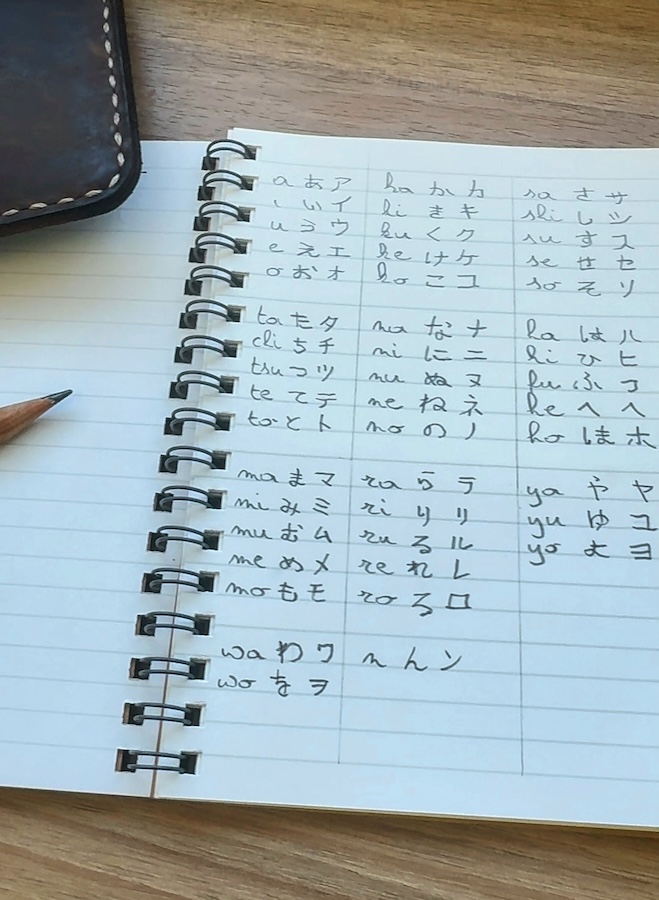

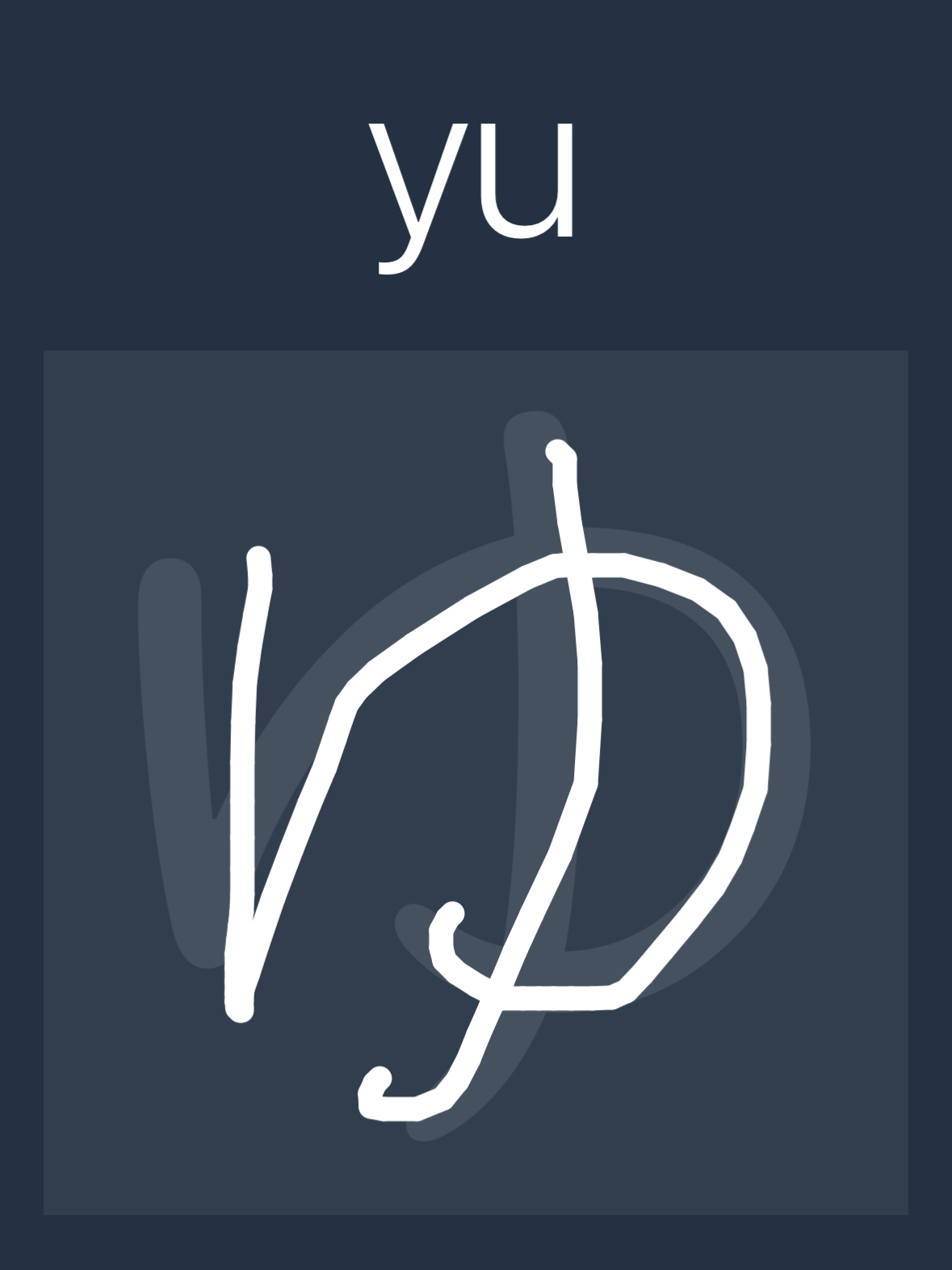

How to learn. This is very personal, but what worked for me was doing two things. First I loved the app 'Japanese!' to learn the 2 simple writing systems, plus a good set of basic words and grammar principles. There is something about the way of teaching that made the words stick better than other apps like Duolingo. Secondly, I would note down learned words, grammar principles, and short handy phrases (notes). Doing this I learned the very basics relatively quickly and it gets very fun and rewarding to apply those basics as much as possible.

Japanese Kitchen

Traditional Japanese. When I think back of Japanese food, I think of rice, seafood, sushi, rice, soy-based products like tofu, miso soup, rice, pickled veggies, ramen, soba and yes, rice. Ingredients tend to be very fresh (it's very seasonal bound), simple flavoured, and neatly presented in various cups and plates with a lot of attention to detail. Not knowing all ingredients and discovering them is part of the fun.

Kaiseki & washoku. Kaiseki is basically Japanese fine dining, and very much recommended to do at least once. It's a multi-course meal where every dish is meant to highlight seasonal ingredients at the peak of their freshness. Apparently this is called 'washoku', which summarises the Japanese cuisine: food should be balanced (addressing all 5 basic tastes), bound to the seasons, and esthethically presented.

Foreign. Especially in the cities, you'll find a lot of foreign restaurants, especially Italians. Also Chinese, Korean and Thai are very present. In bakeries, patisseries and konbinis you see a lot of French inspiration in their pastries. And of course, the US feel present too as you'll see many McDonald's and KFC's.

Obento and onigiri. On a more practical note, especially when biking across many konbinis, obento and onigiri are very much recommended. Obento is Japanese for boxed lunch, which you can buy in plenty forms in every konbini, as well as heat up and (often) consume in their little seating area. Very handy if you're just hungry, on a budget or on a time schedule. They are surprisingly tasty too. The same goes for onigiri: triangle shaped rice, with some seafood ingredient, and wrapped in nori seaweed, costing the equivalent of 1 euro. Often enough I'd buy 3 of these and call it a meal.

The people

Politeness. All the cliches are true. It's one thing to hear about it, it's another to be surrounded by it. Kids bow to cars when they let them cross the streets. Bowing is common and the degrees at which you bow is carefully considered. Words and grammar change heavily based on desired levels of formality. Cars don't honk. People go out of their way to help you a lot. I would wonder if all this comes from a learned sense of duty or if it's just genuine behaviour in the moment. But then again, it doesn't really matter and I love it either way. You feel cared for as a citizen.

Discipline. Also this cliche is true. Not once did I see a pedestrian cross a red stoplight (and I encountered many), no matter if it’s 2 am or the most desolate crossing in Hokkaido. It’s like the Japanese collectively agreed to follow whatever rule they have without any exception, just to not bother their fellow citizens in the slightest. I was told how their discipline is also heavily reflected in working culture: long hours, long after works, strong obedience to hierarchy, and strong affinity to the company they work for. To the point where companies are engraved in gravestones.

Minimalism materialism duality. Just like 'the American' or 'the European' doesn't exist, the Japanese can also differ greatly. One thing they're known for is their minimalism and frugality, which is noticeable predominantly on the countryside. On the other hand, especially in the cities it's fun to see another side which is much more extravert and indulging. The vibrant city centres are anything but minimalistic and the same goes for its people. You'll see very expressive clothing styles for instance, with many dressing up like real life anime.

Kawaii. A very noticeable fascination of many Japanese people is 'kawaii' (Japanese for cute). It refers to the cuteness which can be found in just about anything. Warning signs of bears in Hokkaido are not particularly frightening. Japanese metal music might have some cute vocal overlays.

Technology. The fascination for technology goes a bit further than what the average European or American is used to. I was told by a hostel host this relates to one of the Shintoism principles (one of the two main religions in Japan next to Buddhism), namely that everything can acquire a soul. Where in many countries people would draw a sharp distinction between animate and material objects, in Japan this is much more grey. For example a tea pot that is passed on for generations can hold great value, acquire a soul, and get buried when it eventually breaks. It's easy to understand then their fascination for pepper robots and tamagotchis.

Biking Practicalities

Infrastructure. Roads are generally good condition. Like elsewhere, crossing big cities can make you lose your sanity as you encounter a billion stoplights. Also, it can be ambiguous whether to ride on the sidewalk or on the road, as both are a common sight. The Shimanami Kaido section is the infrastructure highlight with smooth, dedicated bike paths for 70 kilometres.

Safety. Drivers are among the most considerate for bikers, generally leaving plenty room when passing. Also, I was not honked at once. As for the bike, I did have a small lock with me, but if there is one country where it feels useless it would be Japan. On top, I passed zero areas that felt sketchy in any way. In any other country a gloomy highway night store at 3am would easily feel a bit sketchy. Here it doesn't.

Convenience stores (konbinis). Japan has a vast network of standardised and convenient grocery stores, either 7/11, Lawson or FamilyMart. A konbini is generally present within 5 kilometres (often closer), single floored, and has consistent layouts. In all of them you’ll find a public restroom, an ATM, a microwave, and garbage bins (which is not to be taken for granted in Japan). In about half of them there is also wifi, and a small seating area where you can have the food you just bought, and the possibility to charge your electronics. Nearly all food is wrapped in plastic and processed, yet generally very tasty. They also have tasty boxed meals (obento) which can be warmed up on the spot. Pro tip: onigiri.

Vending machines. The first weeks I would always bring 1 to 1.5 litres of water for the day. But as vending machines are everywhere (1 per 23 inhabitants…) you can safely rely on these, even in the most desolate areas. They have all kinds of fruit minted water, sports drinks, and others in 500ml bottles. Over time I’d generally just bring one of these.

Internet. Essential for route building and accommodation booking on the go. By far the most convenient option nowadays is eSim. Download one of many apps (I used Airolo), buy a pack of gigs, and relax.

Financial Breakdown

Total cost. Obviously very personal and dependent on a billion factors, but my total cost for 6 weeks Japan was about 3000€, averaging about 75€ per day. Broken down, this is where it went.

Transport - 900€ ish

Flight return Paris-Sapporo - 560€. This could vary between 500 and 1000€

Flight in Japan to return to starting point from Fukuoka - 180€. This could vary between 50 and 200€

Train return trip Brussels-Paris - 80€

3 Ferries connecting main islands - 50€ ish

Accommodation - 800€ ish

Wildcamping on 10 of 40 days - 0€

Campgrounds on 10 of 40 days - 10€ on average so 100€

Hostels on 5 of 40 days - 20€ on average so 100€

Hotels on 15 of 40 days - 40€ on average so 600€

Food - 1100€ ish

Konbinis - 20€ per day on average so 800€

Restaurants and bars - about 300€ in total

Other - 200€ ish

Onsen visits

Pokémon cards straight from the source

Random Tokyo visits

Souvenirs

Overall, Japan felt fairly cheap. That's partially because the yen didn't do well last few years, making it considerably less expensive than some years back. Partially because I preferred camping options, or sub 50€ hotels when needed. And because biking allowed me to avoid most public transportation costs.

So while 3000€ is a lot of money, considering it was 6 weeks and a good chunk goes to transport it did not feel too expensive.

Accommodation

Wildcamping. The cheapest. Before I heard conflicting reports on whether wildcamping is allowed or tolerated. I ended up wildcamping about 10 nights in forests, on beaches or in city parks, and I had zero issues. Because it got dark already at 6pm, it's a pretty stealthy experience and I don't think I got noticed once. The downside is that enjoying a camping chair at sunset is no part of it, and you're pretty much stuck to reading in your tent on those evenings.

Campgrounds. In some areas there are plenty, in others not so much. Preferred over wildcamping if in need for a shower or to charge electronics. Prices ranged from 5 to 10€, with one weird exception at 25€.

Hostels. Like anywhere else a great way to meet people. The average price for these was about 20€, sharing a bunk bed and bathroom with fellow travellers. If available these would be my first option generally.

Hotels. Functional, boring, small rooms, great for a good night's sleep. On the right end these can get very expensive, but you'll have plenty budget options too. What I paid ranged from 30 to 50€.

Guest houses, ryokans. Both similarly priced compared to hotels, but more fun. Guest houses are essentially like AirB&Bs, where you rent a bedroom, share the bathroom and living space, and have dinner with the household. This is where any amount of studying Japanese shines. Ryokans are traditional Japanese hotels, where you wear a kimono and sleep on the thinnest of mattresses in a tatami room. In one case there was a traditional dance performance upon my arrival, slightly unsettling but cool to see.

Miscellaneous

Onsen. Lying on the ring of fire, earthquakes and volcanos are very present in Japan. As a result also hot springs (onsen in Japanese) are plentiful, both indoors and outdoors. Especially after a full day of biking, visiting onsen are a welcome activity on dark evenings.

Micro earthquakes. It's a thing. When we hear about earthquakes and Japan, we think about disasters like the one in Fukushima. What I didn't know was that micro earthquakes occur 1500 times per year. The majority aren’t felt, but some of them are. It freaked me out. It wouldn't wake you up, but if you lie awake in a hotel on the 11th floor it is maybe slightly unsettling.

Timezone. Japan adheres to GMT+9 to be in line with various south-east Asian countries like South Korea and Singapore. But as it lies relatively east of those, the sun rises and sets pretty early. This is not great for camping as evenings are generally spent in the dark. However, there is one great advantage for Europeans that can work remotely for a few weeks. A classic schedule from 9am to 5pm in western Europe (GMT+2 like Brussels in summer) corresponds to 4pm to 12am in Japan. This means that one could spend their day in Japan as if it were a holiday, and start their office day from a hotel at 4pm.

Gravestones. When biking across the country you can't look past it. Gravestones are everywhere, integrated as small groups in the average street. It shows how Japanese deal with the dead, not hiding them away in graveyards, but actually integrate them in daily life. It's easy to imagine how the dead remain more 'amidst' the living this way. Symptomatic of the strong working culture, company names are often mentioned on said gravestones.

Toilets. 10/10. The first I did when I got home is investigate the cost to install a Japanese toilet.